Ask Professor Puzzler

Do you have a question you would like to ask Professor Puzzler? Click here to ask your question!

Judah from Maine asks for an explanation of how to negate a compound statement.

We'll explore two possibilities. One is that the compound statement contains an "AND" and the other that it includes an "OR." Let's make up one statement for each possibility.

- It's snowing or it's raining

- Christmas is almost here, and the elves are hard at work.

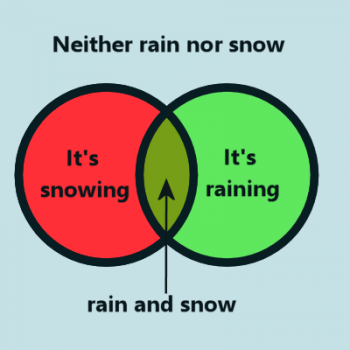

To help you visualize these, I've made Venn Diagrams for each. Let's start with the weather example:

In this example, the red region represents the condition of snow, and the green region reporesents rain. Thus, the greenish-yellow region represents both rand and snow, and the blue region (outside the two circles) represents the condition that it is neither raining nor snowing. This covers all the possible conditions (that is - all the conditions we're concerned about here - there are, of course, other weather conditions like sleet, freezing drizzle, etc, but these are not our concern right now). The possible conditions are:

-

There is neither rain nor snow.

- There is snow, but not rain.

- There is rain, but not snow.

- There is both rain and snow.

Which of those four matches our initial condition? The statement "It's snowing or it's raining" is covered by the red, green, and greenish-yellow regions. That's regions 2, 3, and 4. Therefore, the the logical NOT of "It's snowing or it's raining" must contain everything except those three regions. Or, to put it more simply, it has to be only region 1 - neither rain nor snow.

So the negation of "It's snowing or it's raining" is "It's not snowing and it's not raining." Interesting, isn't it? When you negated an "or" you got an "and." Let's see what happens with our other example:

In this case, the red region represents Christmas being almost here, the green region is elves hard at work, and the greenish-yellow region is both Christmas is almost here and elves are hard at work. The light blue region represents neither of the statements being true.

So which region(s) represent our original statement? "Christmas is almost here, and the elves are hard at work." This is only covered by the overlapping greenish-yellow region.

So if we want to negate this one, we need to figure out a way of expressing everything except the greenish-yellow region. It's tempting to say that the negative of the statement is "Christmas is not almost here, and elves are not hard at work," but that is only the blue region; it doesn't include the red or the green. So instead, we need to say "Christmas is not almost here, or elves are not hard at work." Using an "or" instead of "and" allows us to include all the regions in the Venn diagram.

So our general rule of thumb is, if we're trying to negate a compound statement, we need to make sure that the original statement and it's negation cover every single region of the diagram, without any overlap.

If you've got that, you can go a little crazy with compound statements:

(It's raining and Christmas is almost here) or (it's snowing or the elves are hard at work).

Can you negate that statement?

Yesterday, I answered a question about the Monty Hall Three-Door Game, which you can read about in the previous blog post. After posting the article, I shared it on social media, and commented that talking about this problem feels like wading into a murky swamp, because everyone brings their own assumptions into the problem, and it's tough to guess what those assumptions are.

But I realized, too, that it's not just this problem; it's probability in general. I love probability, and I hate probability. Whenever a district/county/state asks me to write competition math problems for their league or math meet, I know that I need to give some probability problems - everyone expects it! But there's no kind of math problem that I'm more afraid that I'll mess up. I'm grateful for a proofreader to give my problems a second pair of eyes (although my proofreader shares my feelings about probability). More often than not, I'll figure out a way to write a program to function as an electronic simulation of my problem, to verify empirically that I have arrived at the right solution.

Anyway, one of the reasons that probability feels so murky to me is that gut reactions can lead you astray. The Three-Door game is a prime example of how those gut reactions can mess you up. Monty asks you to pick a door, knowing that one of those doors has a prize behind it, and the other two have nothing. After you pick, Monty opens one of the other doors to show you that it's empty, and asks you if you'd like to keep your original guess, or switch to the other unopened door.

Most people's gut reaction is that it doesn't matter whether you keep your original guess or switch to a different guess. This gut reaction is wrong, as you can verify by playing the simulation I built here: The Monty Hall Simulation. For those who are still struggling with this, I'd like to offer a couple different ways of looking at the problem.

The "Not" Probability

We tend to focus on the probability of guessing correctly the first time. Instead, let's focus on the probability of NOT guessing correctly. If you picked door A, then the probability that you were correct is 1/3. This means that the probability you did not guess correctly is 2/3. But really, what is that? It's the probability that either door B or door C is correct.

So if PB is the probability that door B holds the prize, and PC is the probability for door C, we can write the following equation:

PB + PC = 2/3.

Now Monty opens one of those two doors (we'll say C), that he knows is empty. This action tells you absolutely nothing about the door you opened, but it does tell you something about door C - it tells you that PC = 0.

Since PB + PC = 2/3, and PC = 0, we can conclude that PB = 2/3. This is exactly the result which the simulation linked above gives.

Two Doors vs. One Door Choice

Related to the above way of looking at it, try looking at it with a set of slightly modified rules:

- You pick a door

- Monty says to you: "I'll let you keep your guess, or I'll let you switch your guess to both of the other two doors."

Under these circumstances, of course you're going to switch. Why? Because if you keep your guess, you only have one door, but the choice Monty is offering you is to have two doors, so your probability of winning is twice as great. In a sense, that's actually what you're doing in the real game, even though it doesn't appear that way. You're choosing two doors over one, and the fact that Monty knows which one of those two doors is empty (and can even show you that one is empty) doesn't change the fact that you're better off having two doors than one.

Before getting to the question for this morning, I'd like to direct your attention to our simulation of a game show with three doors. It's called the "Monty Hall Game." Understanding this game will be important to thinking about Tracie's question below.

The short summary of the game: There are three doors, and only one of them has a prize behind it. You pick a door. Then Monty opens another door to show you that it's empty, and asks you if you want to switch your guess. What do you do?

Tracie from South Dakota asks, "So if the game show host opened 2 doors for me, would I still have 1/3 probability of winning?"

Hi Tracie, your question highlights a couple of the things about the Monty Hall game that often causes confusion.

- Monty Hall knows in advance where the pot of gold (or new car, or whatever) is. The rules of the game are that he opens an empty door. But if he always opens an empty door, that means he knows where the empty doors are. That's an important concept to understand. He's not being entirely random in his choice of doors to open. There are two empty doors, so if you pick one of them, he picks the other. The only time he's being random is when you pick correctly; in that circumstance he randomly picks one of the empty doors to open.

- This is not a static problem - the circumstances change, and because the circumstances change, the probabilities could change as well. Let me give you an example. Suppose that during Christmas vacation, we decide we want to take our kids sledding. Since I'm not teaching that week, I can pick any day of the week to go. So we would say that my probability of picking Tuesday is 1/7 (there are seven days in a week, and Tuesday is one of them). Now suppose that my wife looks at a weather forecast, and says, "Oh! Thursday, Friday and Saturday are supposed to be cold, with a wind chill of -20 F!" If I use that information in making my choice, what is my probability of picking Tuesday now? It's 1/4, because we've eliminated 3 of the 7 days. That doesn't mean the original 1/7 is wrong - it means that the conditions of the problem have been changed, and so we have to calculate a new probability. This is not, by the way, a perfect analogy to the Monty Hall problem, so please don't try to make it match. The differences are:

- We're talking about the probability that I'll pick a certain day, not the probability that the day I pick is a good one.

- We don't know that there's only one good sledding day.

- My wife is not deviously hiding known information from me.

- Weather forecasts are not 100% accurate anyway.

- There is no #5, but at the end of this post, I'll - just for fun - turn this example into a better analogy for the Monty Hall Game.

Okay, so how does this relate to your question? Number two should be fairly obvious; we have a change in conditions, so there's no reason to assume that the probability will stay the same. The probability of you winning WAS 1/3, but the changing conditions mean we have to recalculate the probability.

But here's the more important issue. Monty Hall can't play the game the way you suggest. Why not? Because if the rules of the game are "Monty will open two empty doors," Monty is going to run into trouble every time you don't pick the right door. Because if you pick the wrong door, how many empty doors are there left for Monty to open? Only one! If you pick one of the empty doors, then there's only one other empty door for him to open.

If he opens two doors, that means you've picked the correct door. So even though your original choice was 1/3 probability of winning, under the new circumstances, you have a probability of 1 (100% chance) of winning.

If you're wondering how that number 1/3 fits into the solution it fits like this: The probability that Monty can open two doors is 1/3 (the same as the probability that you selected correctly). So the number 1/3 is still in there - just in a different place!

If you're wondering why the probability changes in this case, but doesn't when he opens one door, the answer is this: When he opens just one door, he has not given you any information about the door you opened. When he opens two doors, he has (indirectly) given you information about your door.

To add to this, the only way Monty could do the two-door rule would be to have to have a pair of rules:

- If you pick the right door, he will open two doors. (this happens 1/3 of the time)

- If you pick the wrong door, he will open one door. (this happens 2/3 of the time)

The problem with this is: if you know the rules, you can do an always-winning strategy. If he opens two doors, you've automatically won, and if he only opens one door, that means you picked the wrong door, so you must swap. Monty would DEFINITELY not want to play by those rules!

Addendum: If you would like to look at a couple different ways of understanding the Monty Hall problem, you can find more write-up here: The Murky Swamp of Probability.

Sledding in December. Let's say my wife looked at the weather forecast and told me, "Every day but one this week is going to have a wind chill of -20 F, and there will be one day that's going to be sunny and warm. So, randomly pick a day for sledding." (My wife hates the cold, so she would definitely not do something as ridiculous as that!) We'll make the wild assumption for this example that the National Weather Service has 100% predictive accuracy.

So I pick Tuesday. I have a one-in-seven chance of "winning," based on the information I have. Of course, my wife has a different perspective, because she has more information than I do. She knows with 100% certainty whether I've picked correctly or not!

Now my wife says, "Okay, I'll tell you that the following days are going to be -20 F: Sunday, Monday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday."

She's narrowed my choices down to two possibilities. But it's important to remember that this was not a completely random choice. She didn't pick 5 out of 7 days to eliminate; she picked 5 out of 6! She couldn't eliminate Tuesday, because that was the day I had picked, and if she eliminated it, I would be forced to change.

My reasoning now goes as follows: Based on my original information I was given, Tuesday had a 1/7 probability of being the best day for sledding. That means there was a 6/7 probability that one of the other days was the good sledding day. So there's a 6/7 probability that the good sledding day is: Sunday, Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday or Saturday. As a probability equation, I could write:

Psu + Pm + Pw + Pth + Pf + Psa = 6/7

But now my wife has changed the problem. She's changed it by giving me more information: She's told me the values of all but one of those probabilities is zero!

That means: 0 + 0 + Pw + 0 + 0 + 0 = 6/7, which means that Pw = 6/7!

So do I switch my decision to Wednesday? You bet I do! The key to understanding this is that my wife's choice of information to give me is not random, and it therefore significantly alters the shape of the problem.

I hope that this is a helpful answer. The Monty Hall problem is one that repeatedly trips people up. I wonder if my blog post will increase the probability of people not getting tripped up by it!

PS - if you go to the Monty Hall game and change the game settings to 7 doors, 5 hints, that will be the same as my sledding example. Turn on the automation, and watch the percent. If you let it run long enough, you'll see that it eventually settles down to about 85.7%, which is the 6/7 probability we calculated.

Crystal, from Germany, asks: "A stranger sends an email with an attachment for a photo/file what do you do?"

Hi Crystal! Here's a short answer: Don't open any attachments from people you don't know. Now for the slightly longer answer...

There are certain types of files which are relatively safe to open, but even ones that you think would be safe might surprise you. Here's a Q&A that talks about one of those: File Attachments and Viruses. Even if you felt confident that a file type was safe to open, you need to be aware that people can be very sneaky. A file which is named "myimage.jpg?x=5.exe" might fool you into thinking it's a JPEG image file, but actually, because it has ".exe" on the end, it's an executable (program) file. You don't want to be opening that!

So if a complete stranger sends you some sort of attachment on an e-mail, you do one thing, and one thing only: you delete that email without opening the attachment.

Unless...

Unless you work for a business where you might expect to receive e-mails from strangers. For example, suppose you work for a corporation in their personnel department. It's not unreasonable to suppose that you will get e-mails with resumes attached, from people who want to work for your company. I know this happens, because even though I've never advertised that I want to hire someone to work for me, I often get those kinds of e-mails.

So maybe they're legit. But maybe they're not. What to do?

Well, there are a few possibilities.

- Make sure you have the latest greatest virus software installed, cross your fingers, pray, and open that word processor document (Microsoft Word has a feature which causes documents from the internet to be opened in an uneditable "safe" mode, which makes it less likely that the file will give you problems, but I won't suggest that it decreases the probability to zero).

- Contact the person and tell them that you don't accept electronic resumes, and...

- Ask them to mail you a printed copy.

- Give them a fax number, and ask them to fax the document to you.

- Contact the person and ask them to put it into Google Docs, and share it with you.

Obviously, all but the first of these options result in hassle for everyone involved, so most people wil choose option 1. And under certain business circumstances it's impossible to avoid opening attachments from strangers. So if you're in a business situation where you have to open docs from strangers, make sure your virus software is up-to-date!

By the way, you can call me paranoid, but I'm even cautious about opening attachments from friends. After all, what if their computer is infected with a virus? Then their attached file could be infected as well, and they wouldn't even know it! It's like having chicken pox - you are contagious even before you know that you've been infected.

Fourth grader Zaq asks the question, "If 6 times 6 equal 36 why doesn't 7 times 5 do the same?"

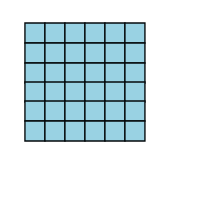

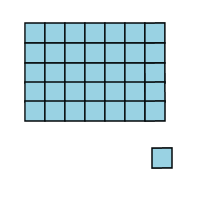

That's a great question Zaq. One of the easiest ways to understand multiplication is to think of it with pictures. Below, I show a picture of a 36 boxes in a great big square. The square has six rows and six columns.

We say that 6 x 6 = 36 because if you have six rows, and each row has six objects in it, that's a total of 36 objects.

You can check it for yourself, by counting up all of those individual boxes in the picture. You'll find that there really are thirty-six of them.

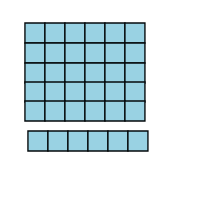

But what about 7 x 5? If you had five rows, and there were seven objects in each row, would there be 36 objects? Well, let's find out. First, I'm going to take the row off the bottom, which will give us five rows instead of six.

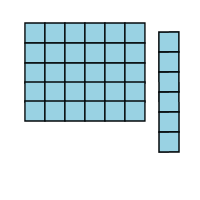

Now I'm going to take that row and rotate it around so it'll fit on the side of the picture.

Uh oh...you see what's going to happen, right? We're going to have an extra block! There are two many rows in that group of boxes, so there'll be one poor little box, all stuck by himself, that doesn't fit into the picture.

You might also be interested to know that that "one less" idea also works whenever you multiply a number by itself: 7 x 7 is 49, but 6 x 8 is one less than that. 10 x 10 is 100, but 9 x 11 is one less than that. 12 x 12 is 144, but 11 x 13 = 143. It's easy to see why that is; whenever you try to take a perfect square and turn a row into a column like we did above, you'll end up with one extra block!

And someday, you'll take an alegbra class, and you'll learn a different way of explaining why that works, but for now, hopefully you'll find the picture a good way of understanding it. Thanks for asking!