Ask Professor Puzzler

Do you have a question you would like to ask Professor Puzzler? Click here to ask your question!

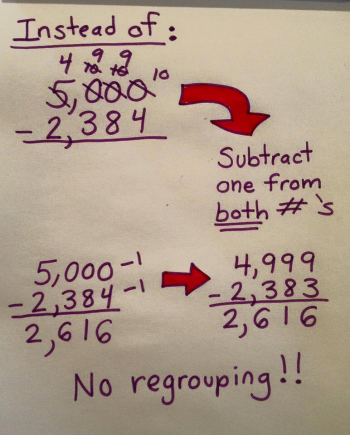

Erin shared the following image, and wants to know if this works. (Click on the image to see a larger version).

Well, Erin, there are really two questions here, and I'm going to try to answer both of them. The first question is the one you asked - Does it work? The second question is one you didn't ask - Is it practical?

Does it Work?

When you ask if it works, I assume you really mean, "Does it work all the time? Or just for this specific example?"

The answer to that is, yes, it always works. I can show you some simple algebra to help you see that this always works.

Suppose you have the equation A - B = C (In this case, A = 5000, B = 2384, and C = 2616)

If we subtract 1 from the number we start with, and the number we're subtracting from, we get:

(A - 1) - (B - 1). If we distribute that negative in front of (B - 1), we get an equivalent expression: A - 1 - B + 1. But the -1 and the +1 are like terms which can be combined, to give A - B, which is still C. So yes, this always works.

What's more, an altered version of this process works with addition:

Suppose you wanted to add 9999 + 4352. Add one to 9999 to get 10000 and subtract one from 4352 to get 4351. Now do 10000 + 4351, and you have 14351.

Is It Practical?

If you are trying to do the problem mentally, then yes, I would say this is practical. However, if you're trying to do it on paper, you should consider that it actually takes more writing to write the entire problem over again, instead of making the few marks required to indicate where you've borrowed. Of course, if you don't understand regrouping/borrowing, then the method shown here will be very appealing to you, even if it takes more writing.

I was trying to think of a real world application where this would be useful, and it didn't take much thought. Suppose I'm at the store, and I have a ten dollar bill. I want to buy an item that costs $3.54. What will my change be?

Instead of mentally trying to do $10.00 - $3.54, I can mentally do $9.99 - $3.53 = $6.46.

Not bad.

William asks us: "Do you have any legal term word searches?"

The short answer is: Not many. You can see what we have by clicking this link, which takes you a search page for the word "legal" in our printable worksheet pages: Legal Search. If you have a specific legal term you're looking for, you can try putting that word in the search bar to see what comes up, or try searches like "law" or "court."

That's the short answer. The slightly longer (but not much longer) answer is: Creating word searches from your own vocabulary lists is simple and easy to do. The capability to create your own word searches starts with a tiny investment of $4.95 to get a Pro Membership on the site. Once you have a Pro Membership, you will have perpetual access to the control panel which allows you to create not just word searches, but also jumbles, mazes, and other content.

To learn more about how you can use your Pro Membership to create your own Word Searches, click here: Video tutorial.

Once you're ready to start, you can go here to buy your Pro Membership. When you do, consider spending an extra $4.95 to remove ads for one year, and help support this educational site!

Angelika from the Philippines wants to know "How to locate the topic sentence."

Well, Angelika, first we need to determine what a "topic sentence" is. A topic sentence is a sentence that summarizes what a paragraph (or essay) is about. In theory, every paragraph is about a single topic; a change in topic is how we recognize that we should have a change in paragraph.

So if you want to find the topic sentence, you need to be asking yourself, "What is this paragraph about?" Then you look for a sentence that summarizes that idea. Once you've found that sentence, you've found the topic sentence. More importantly, though, you know what the paragraph is about, which is the main goal!

Where is the topic paragraph usually found? Well, that depends on the type of writing. If you are reading a technical document or a persuasive essay, you are more likely to find the topic sentence at the beginning. But there's no guarantee that you'll find it in any one location. Let's look at a couple example paragraphs.

Dishwasher repair is a complicated process. Before you can begin your repairs, you need to take the dishwasher apart. Then you need to understand which part is broken. Once you've found the broken part you need to decide if it can be fixed, or if you need to order a replacement part. Then comes the process of removing the broken part and installing the new one, which might require you to remove other parts as well, just to get at the broken part. Now you have to remember where those parts go so you can put them back in the right place after installing the replacement part. Then you have to put the whole assemblage back into positiion and test it out.

So, what is this paragraph about? It's about repairing a dishwasher. But, to be more precise, it's about the challenges you'll face while doing the job. Which sentence indicates that repairing a dishwasher is challenging? The very first sentence! That's your topic sentence.

Here's another example.

Every morning the alarm went off at 4:30, and John mumbled and stumbled and grumbled out of bed to start his work day. But getting out of bed wasn't the worst part of the job. John's co-workers were even crankier than he was at 5:00 when they arrived to open up the store. Early morning was always a hassle because nobody ever did cleanup properly the night before when the store was closed for the night. A spilled soda on aisle seven, a meat freezer that was left open, a container of broken light bulbs in aisle twenty-two; if it wasn't one thing it was another. And all that was before the customers even arrived - at 7:30 a mob of demanding, insulting, greedy, snarling people stormed through doors, and the day just went downhill from there. John really hated his job.

Do you feel like you have a good sense for what this paragraph is about? If we look at the first sentence, we see that it's about John getting up in the morning. Is that what the entire paragraph is about? No, of course not! It's also about what happens when he gets to work, and what happens when the customers arrive. So that first sentence is probably not the topic sentence.

So what is the paragraph really about? It sounds like it's mostly about how miserable John is in his job. Do we have a sentence that says this? Sure! It's the last sentence in the paragraph: "John really hated his job." Does that sentence do a good job describing what the paragraph is about? It sure does!

Does every paragraph have a topic sentence? That depends on the type of writing you're doing. If you're doing a persuasive essay or thesis, then probably yes. If you're writing a narrative like the one above, not necessarily. For example, suppose the writer of the "John" paragraph had left out the sentence "John really hated his job." That wouldn't have changed the meaning of the paragraph much; the reader would probably have inferred that the topic of the paragraph is how miserable John is in his job. However, the paragraph never explicitly states the topic in a sentence.

And that's okay...for that type of writing.

I'd like to begin this post by saying, our world is filled with complex issues - societal, religious, political, scientific, etc., and sometimes we do a lousy job discussing complex issues; we think that a complex issue can be summed up with a "facebook meme", and that once we've seen a tiny little sound bite about a subject, we know everything we need to know on that topic.

Sometimes, we need to have a conversation about the nature of our conversations, and that can be difficult, because we learn by example, and so talking about the nature of our conversations requires us to have specific conversations to analyze. Once I pick a particular conversation to examine, you'll be tempted to assume I'm writing about the topic of the conversation, rather than the nature of the conversation.

This problem has kept me from writing this post for a long time, because if I use something like race relations, gun control, religious freedom, government spending, gender equality, or any other hot topic as my example, people who have strong feelings (one way or the other) on the subject won't be able to see past the specific topic to the nature of the conversation.

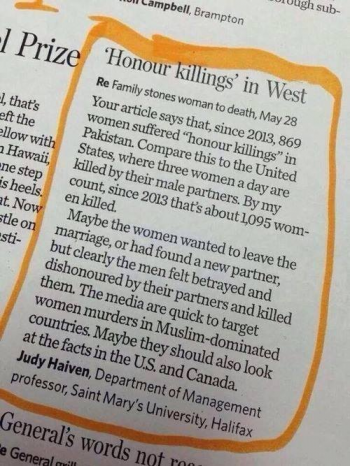

But now, I have the perfect sound bite to talk about. It's about something that really isn't a hot topic (after all, I think we all agree that domestic violence is a bad thing no matter where it crops up in the world), so we can look at an example of irrational sound-bite conversation on this subject, and hopefully people won't get bogged down in the specific topic, and will be able to focus on the nature of the "conversation."

The image shown here has been cropping up on facebook since last October (click on the image to see it full size). I've left it entirely as-is. I thought about blocking out the author's name, because the letter is rather embarrassing for a "professor" to be writing, but then I realized - first, she posted it in a public place (newspaper), and second, more than ten thousand people have "liked" or "shared" this on facebook, so there's not much point in trying to protect her privacy, or keep her from embarrassment.

Declaration of Authority

The first thing I'd like to point out is that no one writes letters to the editor signing them "Joe Shmoe, Dental Hygenist at Canal Street Dentistry," or "Ferdie Jones, Truck Driver at Waste Management Services," because they know that doing so will not provide any weight to their opinion (unless it's on the subject of teeth, or the subject of garbage), but people in positions of academia are happy to post things like "Judy Haiven, Department of Management professor, Saint Mary's University, Halifax", because it provides an aura of academic wisdom and experience, and few people will stop to ask, "What does 'Department of Management' have to do with having special knowledge or insight about conditions in Pakistan?"

In addition, the "declaration of authority" implicit in the signature will cause people to be less cautious when it comes to trusting the content of the writing. Being a professor results in people expecting you to be able to reason and argue logically, but being a professor does not guarantee that you make use of those capabilities.

And of course, as you're reading this you should be thinking, "Wait a minute...who is this 'Professor Puzzler,' that's writing this post, anyway? What is he a professor of? Is he really a professor?" I'll leave you to track down the answer to that question; it's not hard to find the information on this site.

Removal of Context

The second thing I'd like to point out has nothing to do with the actual letter. It has to do with the fact that it has been shared thousands of times on facebook. When the letter was written, it had a context. You can't see the context, but you can tell what it context was; it was a letter to the editor in a newspaper. Which means the author had a reasonable expectation that people who read her letter would also have read the article it was about, and would therefore have a frame of reference in which to understand her response.

Through no fault of hers (probably), the letter has been removed from its context by people sharing it on social media. Do you know the newspaper in which the original article appeared? Probably not. Have you read the article which she was responding to? I expect you haven't. Furthermore, I would guess that of the thousands of people who have shared this, the vast majority have never read the original article.

And this has become the nature of our sound bite conversations: we learn about issues without the context of their larger complexities, and we learn about issues by reading only one side of the conversation.

This issue is painfully obvious in the world of politics, where both left and right grab opposing sound bites out of context and then respond to the sound bites as though they are actually a full conversation. And we all eat it up, because it helps to confirm our pre-existing biases.

Wouldn't it be great if - before posting/liking/sharing something on social media, we were required to read at least one article each from opposite sides of the issue, so we could gain a deeper understanding of the larger complexities of the issue?

Now let's talk about the actual letter, because there are a couple of glaring statistical and logical fallicies in it (hence the embarrassment to Professor Haiven!)

Misuse of Statistics

The letter purports to do a side by side comparison of what's happening in Pakistan to what is happening in the United States of America. Comparing the number of times something happens in Pakistan each year to the number of times it happens in the United States.

The author of this letter needs to learn a little thing we call "per capita" - per capita means "per head" or "per person." If we want to have a meaningful statistic, we need to take our total and divide it by the population, and then do our comparison. Let me show you how silly this can get if we don't do our statistics properly:

Alice lives in town A, which has a population of 2000, and Betty lives in town B, which has a population of 200,000. Listen to this conversation:

Alice: In our town we have 40 geniuses.

Betty: That's nothing! In our town we have 50 geniuses! Clearly the residents of B are smarter than the residents of A!

What is wrong with this? Obviously, 40 out of 2000 is a much higher rate than 50 out of 200,000! Divide the number of geniuses by the total population, and you have a per capita figure, and this is what Betty needs to be comparing.

40 / 200 = 0.2; 50/200,000 = 0.00025.

Now when we compare, we see that Alice's town has a much higher ratio of geniuses.

Professor Haiven should automatically know and understand that she can't compare what's happening in Pakistan to what's happening in the United States without doing some per capita calculations. And yet, that's what she's done. The fact that a college professor doesn't know this isn't just embarrassing - it's downright bizarre!

Am I going to do those calculations for you? No! You can look up the population of Pakistan in 2013, as well as the population of the United States, and I've shown you how to do the per capita calculation, so you can figure it out for yourself. The big question is: will you figure it out for yourself?

Herein lies one of the problems with our sound-bite conversation style: taking the time to actually research something is not really worth our time, so we don't bother. Instead we just accept whatever is spoon fed to us.

This issue of misusing statistics is a huge problem in our standard conversation style about any hot button topic; I see misuse of statistics in just about any discussion of race relations, gun control, etc. Statistics are great, because a little bit of math goes a long way toward making our point believable, and if people aren't paying attention, we can make numbers and statistics say anything we want them to.

Just because Professor Haiven can multiply 3 times 365 to obtain 1095 doesn't mean that she actually knows the significance of that number. But if you're going to read what she wrote, you need to be able to figure out the meaning of that statistic, before you swallow her reasoning.

Changing the Rules of the Discussion

Here's the other glaring issue here. Clearly, the writer of the original article was writing about something called "honor killings." The author must have had some sort of definition of what an "honor killing" is. You can do some research if you want to find out more about how that is typically defined (again, here is the problem with removing the letter from its context; we can only make educated guesses about the definition the original author was using!). What you will find is that the way in which "honor killing" is typically defined makes it a subset of domestic violence - in the same way that granny smith apples are a subset of apples.

Professor Haiven appears to have taken umbrage with whatever definition the original author was using, and she replies (in essence) "All domestic violence that results in death is a form of honor killing." What she's doing here is she's arguing about definitions.

She's welcome to have her own definition, of course, but if she's going to change the definition, she needs to understand that the statistic that went with the article's definition is not the statistic that goes with her definition. Is it like comparing apples with oranges? Yeah, it kind of is. Or, here's a more accurate comparison:

Clarence lives in town C, and Doris lives in town D (we'll assume they have the same population). Here's the conversation:

Clarence: Our town produces 100,000 Granny Smith apples every year.

Doris: Well, that's just ridiculous. Here in town D we actually have a "Granny Smith," and she loves all kinds of apples, so we don't hold with such silly designations; we just call all apples "Granny Smiths!" Furthermore, our town produces 1,000,000 granny smith apples every year, so clearly we have better apple production than you!

What's the issue with this conversation? I think it's fairly obvious; Doris has tried to change how we define granny smith apples, and yet she's still using Clarence's statistic which is based on his definition, not hers. In so doing, she has completely disregarded the fact that town C probably produces Cortland apples, red delicious apples, gala apples, etc.

Another way of putting it; Doris has started a new conversation, and is pretending that Clarence was participating in her discussion based on her rules.

If you change the definition, you have to recalculate any statistics based on the old definition, otherwise you're making no sense whatsoever. If you don't think that's what Professor Haiven is doing, you should probably go back and read her letter again.

And herein lies another problem with our sound-bite conversation style; we want to receive something without having to think carefully or deeply about it, and when we choose not to carefully evaluate the logic behind a statement, we are inviting people to mislead us.

When combined with the removal of context, this "changing the rules" issue becomes even more ugly, because now you've prevented the original writer/speaker from saying, "Hey! That's not how I defined my terms!"

Argument vs. Conclusion

You know what's really odd about this letter? If you remove all the stuff in Professor Haiven's letter that is illogical, you're left with one sentence - essentially - "We should be concerned about domestic violence in the west," and that's a statement I can get behind 100% - I completely agree with it!

In our world of sound bite conversations, whether or not you agree with the conclusion seems to be all that matters. This is a dangerous pattern of conversation, because it is actually a way of saying that rational thought doesn't matter. You actually can't have a real conversation if you don't care whether the things you say are true or not.

This has become so prevalent in social media. Someone shares a post that is irrational, illogical, misuses statistics, etc., but woe to the person who says, "But this is completely bogus reasoning because..."; the response typically is, "Yeah, but they make a good point, so shut up."

No, they really don't make a good point. The fact that you agree with their conclusion doesn't mean that they've made any point at all. And if we have become incapable of recognizing the difference between an argument and a conclusion, we have become incapable of discussion.

Even though I agree with Haiven's conclusion - domestic violence is something we should be concerned about here in the west - I would never share this image as a way of defending that conclusion, because she hasn't added anything useful or rational to the discussion on violence.

Conclusions

What can we learn from this letter that's been traveling around the internet?

- Content without context is next to useless.

- If you pass on information based on incorrect statistics, you're part of the problem.

- If you pass on information based on illogical reasoning, you're part of the problem.

- Taking the time to research something may be inconvenient, but without that step, there really isn't a conversation to be had.

- If you don't take the time to evaluate logic and reasoning, you open yourself up to deception.

- Having a title before or after your name doesn't automatically guarantee that you are a reliable source of information.

- Just because you agree with someone's conclusion doesn't mean you give them a pass on irrationality in their arguments.

We can also learn the following specific lessons in reasoning:

- Statistics about populations of people require per capita calculations.

- A change in definition requires a recalculation of statistics.

And hopefully, we can take these lessons into the hot topics that we reguarly discuss in this sound-bite world of ours!

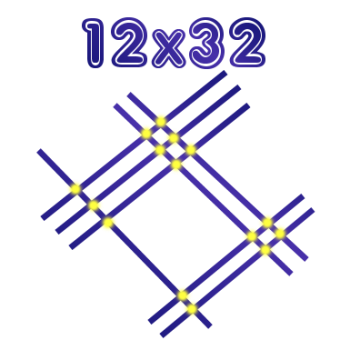

You've seen the videos, you've probably shared them on Facebook or other social media...the videos that tell you, "This is how the Japanese multiply numbers!"

Except...do they really?

First, here's an example:

The question is, how do you multiply 12 x 32 the Japanese way?

Well, supposedly, the Japanese solve this by drawing one line diagonally from the left down to the right, followed by a pair of lines going in the same direction. The one line, followed by the two lines, represents the number 12.

Similarly, three lines are drawn together from the left up to the right, followed by two more lines from the left up to the right; these sets of lines (3 and 2) represent the number 32.

Now you draw a circle around every intersection point, starting over on the right. There are 4 intersection points. That means that the last digit is 4. In the middle there are six intersection points (at the top) and two more at the bottom, making a total of 8. Thus, the middle digit is 8. Finally, there are 3 intersection points on the left, so the first digit is 3.

Therefore, the answer is 384.

I'll give you a second to use your old algorithm (or your calculator!) to verify that this is correct.

Does this always work? Well, yes...and no.

The videos that display this process rarely show what happens if the sum of your intersection points is greater than 10. If that happens (which, really, why wouldn't it?) your process is a bit more cumbersome, and you have to transport a group of ten dots as a single dot in the next place value. In other words, you have to carry.

That's not a big deal, though; you already have to carry with your algorithm. So what's the problem with this algorithm? Well, the people who make these videos are very careful to make sure they do multiplications with small digits. You'll see things like 12 x 32, or 113 x 21, but you'll never see one of these videos with 978 x 88.

Why not? Gee...I don't know...why don't you try drawing the diagram for that problem, and see what it looks like. While you're busy drawing that diagram, I'll solve about five more multiplication problems. You'll need to draw forty lines, circle and count 201 intersection points, and meanwhile, I've moved on to my division lesson, because I got tired of waiting for you.

Do the Japanese do this when they're multiplying? Of COURSE NOT! I don't know if any Japanese teachers actually show this to their students (read comments on videos and you'll find people saying things like, "I taught math in Japan for 25 years and never saw this.") but if they do show it to their students, it's only as a way of visualizing place value in a different way; nobody actually expects their students to use this as their go-to multiplication algorithm.

And yet, wherever you see videos like this, you'll see comments from parents saying things like, "If I had learned it this way, I wouldn't have ever had problem with math," or "I'm going to meet with my kid's teacher and ask why in the world she's not teaching it this way!"

Oh dear! Please give your child's teacher a break! Let them teach math, and don't force them to spend an afternoon explaining to you why the latest craze to hit the internet isn't actually even slightly useful as a multiplication algorithm.

And if you got fooled by the "Japanese Multiplication" video, odds are good you also got fooled by the "Oh noes! Have you seen how Common Core does subtraction????" videos, so you'll want to read our post about "Common Core" Subtraction.