Ask Professor Puzzler

Do you have a question you would like to ask Professor Puzzler? Click here to ask your question!

The following question comes to us from fifth grader Savannah, from Ruston. "How do you convert units with exponents using the method 'king henry doesn't usually drink chocolate milk'?"

Hi Savannah. "King Henry Doesn't Usually Drink Chocolate Milk" is what we call a mnemonic; it's a phrase that's designed to help you remember something important. In this case, what we're trying to remember is the prefixes for metric units. The prefixes all begin with the same letters as the words of the mnemonic, as shown below, with an example unit:

King ⇒ kilo ⇒ kilometer

Henry ⇒ hecto ⇒ hectometer

Doesn't ⇒ deca ⇒ decameter

Usually ⇒ Unit without prefix ⇒ meter

Drink ⇒ deci ⇒ decimeter

Chocolate ⇒ centi ⇒ centimeter

Milk ⇒ milli ⇒ millimeter

So let's say I had 20 hectoliters. How would I convert that into milliliters? King Henry will help me remember the order of the units:

kilo ⇒ hecto ⇒ deca ⇒ unit (without prefix) ⇒ deci ⇒ centi ⇒ milli

If I want to go from hectoliters to milliliters, I'm moving 5 prefixes to the right, so I'm going to multiply by 105. Thus, I have 20 x 105 = 2000000 milliliters.

If I wanted to convert 5 centimeters to decameters, I am moving the opposite direction through the units, and I'm moving 3 prefixes. So this time I divide (because I'm moving in the other direction) by 103. 5/103 = 0.005 decameters.

One problem with this mnemonic is that both deca and deci begin with D, so you still have to remember which word goes with which prefix. I would try to remember that both "drink" and "deci" have the letter i in them, and that may help you out.

Good luck with your unit conversions!

"Can you explain terza rima and give an example?" ~Anon, grade 5

Terza Rima is an Italian phrase that means "third rhyme." It's a specific way of rhyming lines in a poem. I think of it as sort of a revolving door of rhymes. In each stanza of a Terza Rima poem, there are two lines that rhyme, and one line that does not. The line that doesn't rhyme provides the rhyming syllable for the next stanza. Even though it doesn't rhyme with other lines in that stanza, it provides a connection to the next stanza, thus building the whole poem into a progressive, seamless whole.

In a Terza Rima poem, the last stanza often has two rhyming lines (that's called a couplet).

In other words, the rhyme scheme looks something like this:

ABA - BCB - CDC - DD

If you wanted more than four stanzas, you could chain together as many stanzas as you want in this format.

If you have a hard time following that explanation, here's a silly poem I wrote just for you, that uses the Terza Rima rhyme scheme:

Candy Land

I dreamed the world was made of cookie dough.

The skies were filled with cotton candy clouds,

And from them blew a storm of whipped-cream snow.

The fields of chocolate, farmers left unplowed;

The stalks of candy-cane grew everywhere,

And gum-drops grew on bushes, low but proud.

Oh, nothing in this world seemed quite so fair

As pine tree branches bowed with sugar cones -

Enough for all the hungry crowds to share.

A whiff of spearmint on the wind was blown

O'er milk-shake streams and maple syrup lakes.

I shouted from atop my candied throne:

"This world of ours, it really takes the cake -

If it's a dream, I do not wish to wake!"

Copyright 2017 by Douglas Twitchell

Incidentally, Robert Frost wrote a terza rima sonnet titled "Acquainted with the Night." In addition, his poem "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" is not Terza Rima, but it's a very similar "chained" rhyme; each stanza has four lines. The third line doesn't rhyme with the others, but it does introduce the rhyme for the next stanza. The rhyme scheme looks like this:

AABA - BBCB - CCDC - DDDD

B.R. asks, "Can you explain what mechanical advantage is?"

Hi B.R., I'll give it a shot. Not knowing how much Physics background you have, I'll try to explain it in simple terms.

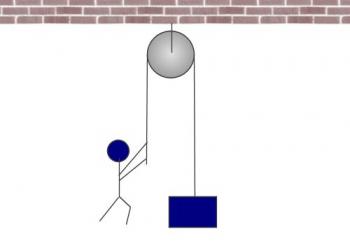

First of all, I'd like you to consider the following arrangement, which is a person pulling on a rope, which runs over a pulley, and down to an object with a weight of 400 Newtons (that's about 90 pounds, if you're used to using English units).

Now, when we talk about someone pulling on something, we're using the concept of a force. Forces are measured in Newtons (or pounds). If the object has a weight of 400 Newtons, that means the person holding the rope has to pull with a force of 400 Newtons in order to keep the object from speeding up or slowing down. If he pulled with a force greater than 400 Newtons, the object would begin accelerating upward. If he pulled with a force less than 400 Newtons, the object would begin to accelerate downward.

This system has a mechanical advantage of 1. This means that on one end, the person applies a force that is equal to the force at the other end of the system. 400 / 400 = 1.

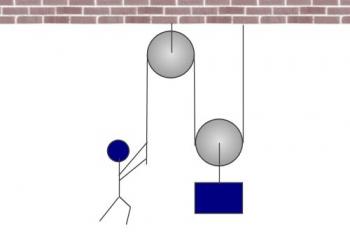

So let's take our pulley system and make it just a little more complicated. Here I've put a second pulley at the bottom, and attached the rope to the ceiling. The object hangs from the lower pulley.

Now, one of the things that's important to understand is that if the man pulls with a force of 400 Newtons, there is tension in the rope, and the tension is the same everywhere along the rope. That tension is also measured in Newtons, and it is 400 Newtons. But here's where it gets interesting. Look at that lower pulley (that the object is hanging off). What is the tension in the rope to the left of the pulley? 400 N, right? What is the tension in the rope to the right of the pulley? It's also 400 Newtons. This gives a total of 400 + 400 = 800 Newtons. The upward force on the object is double the object's weight. This object is going to accelerate upward, even though in the first scenario, it would not have accelerated.

So if the man pulls with a force of 400 N, the output force is 800 N. The mechanical advantage is 800 / 400 = 2.

Incidentally, this means that the man could hold up an 800 Newton weight by applying a 400 Newton force. That's pretty impressive!

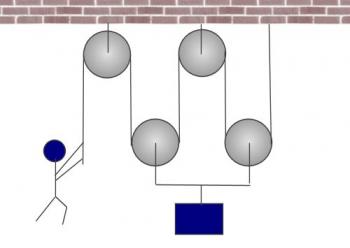

You could add more pulleys to the system, as shown here:

In this case, if the man is pulling with a force of 400 N, that means that there is 400 N of tension all through the rope, and so each of the lower pulleys has an upward force of 800 N, which means that the object (which is being supported from those two pulleys) has an upward force of 1600 N applied!

So the mechanical advantage is: 1600 / 400 = 4.

It seems like this is a win-win situation; you get better results by adding more and more pulleys. So why not add five hundred pulleys? If you did, you could hold up a 400 Newton object by applying a tiny, tiny force (less than 1 Newton!). So is it really a win-win situation? Not exactly. You see, there's a tradeoff for mechanical advantage. The tradeoff is the distance you pull the object. Take a look at the first diagram. If the man pulls the rope down 1 meter, the object will rise 1 meter.

But what about the second diagram? What will happen there? Well, if the man pulls the rope down 1 meter, that meter is evenly distributed on either side of the lower pulley. Which means that pulley will only rise 0.5 meters. And therefore, if he pulls down a meter, the object only rises half a meter.

What about the third diagram? In that scenario, if the man pulls the rope downward 1 meter, that meter gets evenly distributed among four sections of the rope (one on either side of the two lower pulleys). In other words, the object only moves 0.25 meters.

So, if you had 500 pulleys, you'd be in the very interesting situation that you could easily lift a 400 Newton object, but it would take you a long time to do it; for every meter you pulled the rope down, the object would only move 2 millimeters!

There are many other kinds of machines: screws, wedges, levers, axle-and-wheels, and inclined planes. For every machine, there's a tradeoff; you can make the work easier, but in doing so, you end up extending that effort over a longer distance. An inclined plane is another easy one to picture. Imagine trying to lift a grand piano 1 meter straight off the ground. Can't do it, right? But if I made a long ramp, you could push the piano up. Much easier than lifting, but the tradeoff is that you have to push it a whole lot more than 1 meter!

When I was a child, the newspaper meant one thing: comics! My brothers and I would race to see who could get the section containing the "funny pages" first. The rest of us would have to wait impatiently while the winner guffawed over the antics of Beetle Bailey, Nancy, Andy Capp, and many others.

As I grew older, I started to get more curious about what was going on in the world (read my previous blog post about sixth grade to find out why I got interested in current events), and so I began to look at the first section of the paper to see what the news headlines were, and maybe read a story or two. I might start in reading a story about a hostage situation on page one, and when I'd get to the end of the column of print, I'd see a bold line of text that read: "See HOSTAGES, Page 8". Dutifully, I would flip to the end of the section to finish the story. While I was there on page eight, I would notice other news stories.

These stories were not about hostages or economics or foreign policy; they were stories about an actor who broke his leg on the set of his newest movie, or about a man who lost his dog and found him three days later in a dance club smoking a cigar and flirting with a waitress.

One thing I understood without having to be told: the page one stories were important news, and the page eight stories, while they might be interesting, were just fluff. They were human interest stories that might catch my curiosity, but they didn't have any broader implications than that. The dog in the dance club was not going to significantly affect my life, or the life of anyone else except the dog's owner - and maybe the dance club owner and employees.

Sometimes those page-eight stories would creep onto the first page; there would be a column that devoted an inch or two to a page-eight story, followed by, "See DANCE DOG, Page 8". But these column inches were always below the fold, and I knew before I started that it was actually a page-eight story, even though it started on page one.

I didn't think about it at the time, but I was putting trust in the journalistic integrity and capability of the people who organized the articles in the newspaper. I was trusting that the most important stories would show up above the fold on page one. The corrolary to that was, if I never got around to reading page eight, it wouldn't really matter.

These days, a very large chunk of the population doesn't read print newspapers (including myself). And for people who read news online, there is no such thing as a Page-Eight Story, because the internet isn't organized into pages in the same way that a print newspaper is. There is no page one, page two, page three, etc. There is only "the home page" and "all the other pages." So how do news sites indicate which stories they think are most important?

Web development has stolen terminology from newspapers; just like a newspaper, we talk about content being "above the fold" or "below the fold." Of course, a website doesn't have actual folds, but when we say "above the fold," we're talking about content that is visible immediately, without scrolling. Content that is below the fold is content which you can't see without scrolling downward.

For example, to use a major news site - The New York Times - when I visited their home page yesterday, the above-the-fold story was about US relations with North Korea. The story about everyone waiting for a giraffe to give birth on live camera was below the fold. In fact, it was way below the fold. I had to scroll down at least three full pages to find it.

Last week, while the above-the-fold story was about Mosul, if you wanted to read about people going bananas over Kellyanne Conway putting her feet up on the Oval Office sofa, you had to go well below the fold to get it.

This is what I expect to see. Mosul and Korea are page one stories. Giraffes and Kellyanne's feet are page eight stories. Bravo, NYT! In my opinion, you did your job, and you did it well.

So why is this a eulogy for the page-eight story, if it still exists, just in a different form?

Because the page-eight story has been murdered. It has been brutally butchered and left for dead, dragged unceremoniously onto the front page, like the dead mouse your cat dragged in from the outdoors and plopped onto the sofa. The culprit in this vicious homicide is not the mainstream media. The culprit is you, and the culprit is me. We are all the perpetrators of this heinous crime. You probably didn't realize it, but you need to realize it, so you can stop perpetrating it.

Let me explain. Did you realize that most people don't care what's happening in Korea? Or Mosul? Most people would rather talk about feet on sofas and giraffes giving birth. These stories are the grown-up version of racing for the comic pages. So here's what happens on a daily basis:

The Newspaper Readers

The people who actually visit news websites scan through headlines, read an article here or there, and then think "My friends would like to read this story, so I'm going to share it on social media." But which story do you think your friends want to read? The story about North Korea? Or the story about Kellyanne's feet? The answer, of course, is that most of your friends don't want to read about Korea; they want some juicy gossipy story that they can whine about and feel superior about. So you share the page-eight story instead of the page-one story. You don't think anything of it, and it never occurs to you that thousands of other people are doing exactly the same thing as you, and that you are, in effect, turning the page-eight story into a page-one story. That story is the dead mouse that your cat proudly dropped onto the sofa for everyone to see. It doesn't belong on page one. The journalists didn't put it there. You did!

The Social Media Readers

The social media readers get all their news from Facebook. So unless they've got friends who recognize a dead mouse when they see one, they know absolutely nothing about North Korea or Mosul. But they know everything about Kellyanne's feet and giraffe births. It never occurs to them that the journalists behind the story considered it a page-eight story, and hoped that you would take time to read about Mosul before you went on to lesser stories. So they read the story, find it amusing, and probably share it with their friends. So the foot story goes viral, while the North Korea story lies dormant.

The Result

Sooner or later, everyone starts asking the question, "Why is the mainstream media reporting this? This isn't news!" or "Hey! the mainstream media is trying to distract us from important stories. They're *gasp* FAKE NEWS!" In essence, we start saying, "I can't believe CNN/New York Times/Washington Post put this dead mouse on my sofa!"

Uh...NYT didn't put that there. Your friends did. And you did. You are the one who decided a below-the-fold story was more interesting and more important than an above-the-fold story. The journalists did their job, and you undid it!

We need to come to terms with the fact that news doesn't work the way it used to. In the age of social media, we are all journalists. We all make editorial decisions about what's important enough to share, and what isn't. We can't blame the "mainstream media" for bad journalistic choices when we are the ones who have made those bad choices.

Let's resurrect the concept of a page-eight story. Share thoughtful, important stories on social media, and let the below-the-fold stories be a special treat for those people who actually chew their way through the steak and potatoes of the above-the-fold news. Because the page-eight story wasn't intended to be a dead mouse; it was supposed to be a dessert for the faithful few who eat their supper. Be wise about how often you share those stories, remembering that you too are a journalist.

The choice is up to us. The newspapers have always reported page-eight stories, and they're not going to stop just because we've stopped recognizing the difference between the important and the trivial. Be a good journalist in the age of social media.

My elementary school years are a blur of memories for me; months at a time went by that I remember very little about, and then there were moments that stand out vividly in my mind, even 35 years later. For some of those childhood years I struggle to remember what my teachers looked like, or what their names were. Other years I remember the teachers as though I was in their classroom last week.

I remember my sixth grade teacher like that. Mr. Frank Avey. I remember that before we hit sixth grade, we were all scared to death of him, and we didn't want to be in his class. The rumor was that he was an army drill sergeant before he became a school teacher, and he ran his class like he was still in the army. It turns out, he really was in the army before he became a school teacher (though I have no idea if he was a drill sergeant), and he did (sort of) run his classroom like the army. He could be fierce, and he was certainly strict.

But once I got into his classroom, and had spent a day or two there, I knew that I wasn't going to be afraid of Mr. Avey, and I wasn't going to hate being in his class.

What do I remember? I remember that every day at 10 minutes to noon, a current events news program would come on, so at 15 minutes to noon, Mrs. Avey's class (yes, his wife also taught sixth grade at the same school; she was the sixth grade teacher everyone wanted to get!) would come into our classroom (because we had the television) and watch the news together with our class. Then, when the news was over, we'd all have to take a current events quiz over what we'd just watched. It was stressful. Of all the quizzes I ever took, those were the hardest. But I learned a lot about the world that year.

I remember watching Mr. and Mrs. Avey drive up to school in their metallic green Volkswagen bug, and thinking what a cool car that was (I know, it's silly, but I'd never ridden in one of those crazy looking cars).

I remember the classroom getting too loud, and Mr. Avey making everyone put their heads down on their desks for 5 minutes. Oh, what torturous, tedious minutes! I remember my glasses fogging up while my head was down (what weird things I remember!) and I remember being annoyed that I had to suffer this indignity. After all, I wasn't the one who was too loud.

I remember finishing my work early one day, and not having anything to do. Mr. Avey found some work I could do to help him. I felt quite important and helpful sitting at the desk next to his and stapling papers. And then the stack of papers turned into a bin filled with extra things for me to do. I think he labeled that bin "Assistant" or something like that. Oh, didn't I feel special then! He could have labeled the bin "Teacher's Pet" and I probably wouldn't have cared.

I remember that when I graduated from high school, even though Mr. and Mrs. Avey had moved out of state, I got a graduation card from them.

I remember all of these things. And I remember - most vividly - the day I got to ride in the metallic green Volkswagen bug. Here's the story.

Mr. and Mrs. Avey were staunch Democrats. My family was all staunch Republicans. But this was back in the era of American history when people weren't utterly stupid about politics. I know it's hard for people to remember, but there was once a time when people who were Democrats and people who were Republicans actually knew how to talk to each other and get along with each other. Republicans had friends who were Democrats, and therefore weren't about to refer to Democrats as "snowflakes" and "lazy welfare cheats." Democrats had friends who were Republicans and therefore weren't about to refer to Republicans as "bigots" and "uneducated buffoons." Those were the days when people were allowed to have different opinions from one another and still consider each other worth talking to and listening to.

Ah...the good ol' days.

Oh, sorry - where did that come from? Anyway, back to my story.

Mr. and Mrs. Avey contacted my parents one day and said, "We'd like to do something special for Doug. We want to take him to a political rally." My parents knew perfectly well that this was a "liberal" rally, yet they didn't object (insert another good-ol-days comment here)! So one afternoon, I got to climb into that green bug and go on a one-student field trip. I was astonished at how little room there was in the back seat. It was a good thing I was only a sixth grader; my legs were already almost too long to fit comfortably!

We drove to Portland, where I went to dinner with Mr. and Mrs. Avey, and then had the privilege of hearing Walter Mondale speak at a campaign rally. He was, at the time, vice president of the United States under Jimmy Carter, and was running for re-election.

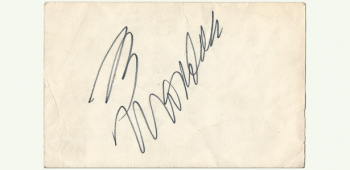

Do I remember anything he said? I do not. Not a word. I remember the excitement, the bright colors, the noise, the crowds. And I remember the strange mix of excitement and nervous tension when the rally was over and Mr. Avey said, "If we go stand over here, maybe you'll be able to get his autograph." The vice president of the United States! I'd never met anyone that powerful! (and don't start telling me that the vice president isn't actually all that powerful; I don't want to hear it!).

My hands were sweaty and trembling, my knees were almost certainly knocking. What an exciting moment it was when I thrust a little slip of paper in front of him, and he scrawled on it something that looked more like "B. Monoah" than "W. Mondale", and then shook my damp little hand before moving on to the next person. The moment lasted less than five seconds, but I haven't forgotten it.

Today I searched through a giant file of papers from my elementary school years to find this scrap of paper. It took a long time to unearth it. Why today? Because this morning's newspaper had the following obituary headline:

Francis L. Avey Jr. (1936 - 2017)

Mr. Avey passed away last week after a "courageous battle with cancer" at age 80.

It's funny, I have thought of that autograph many times over the years, but I've never felt compelled to try to find it until today. And as I studied it over this evening, I realized something important. All those times I thought about Walter Mondale's signature, the sequence was never that I thought of Walter Mondale, and it reminded me of Mr. Avey; the sequence always was, thinking of Mr. Avey reminded me of Walter Mondale.

And so it seems that in the life of one child, a sixth grade teacher truly was more powerful than the vice president.

I hope and pray that I too will have that kind of power in the life of a child. Thank you Mr. Avey, and all the others who have had this power in my life. May God bless you all.